If you are doing what 90% of other websites are doing, probably not.

If you are doing what 90% of other websites are doing, probably not.

The biggest resistance I get from clients involves my trying to get them to post their privacy policies and disclaimers on their websites to comply with the laws and regulations, and to reduce their liability. When they discover that posting these important documents in the footers of their websites will provide them with little or no legal protection, they always point to the overwhelming majority of big companies that post their documents in the footers of their websites.

The “Big Guys” Do It – It Must Be Ok

Unfortunately, more often than not, big companies are some of the worst offenders on the Internet in terms of posting their privacy policies, disclosures, and disclaimers in a way that does not comply with privacy and disclosure laws. Many of them get warning letters from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and some get sued. Using another company’s website as a guideline for your own website or blog makes little sense, especially considering that over 90% of websites do not post their legal documents correctly.

What do the laws and regulations say about posting your website policies and disclaimers?

The following definition applies to almost all Federal, State, and Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) laws and regulations about displaying privacy policies, disclaimers, and disclosures.

The wording and links to such documents must be “Clear and Conspicuous” without giving an exact definition of what “Clear and Conspicuous” is. However, the common definition given by most state and federal regulatory agencies is that the language is “conspicuous” if it is in a contrasting type or color. At a minimum, the font size should be the same as nearby or surrounding text. It should also be displayed such that any reasonable person would notice it.

Posting Requirements for Website Privacy Policies

A website privacy policy is not only required by law for most website owners; it is also required by law to contain specific provisions and to be posted on your website “clearly and conspicuously.”

Here is a partial list of requirements for posting your privacy policy from the California Business and Professions Code 22575: (The California Online Privacy Protection Act [CalOPPA]).

(a) An operator of a commercial website or online service that collects personally identifiable information through the Internet about individual consumers residing in California who use or visit its commercial Web site shall conspicuously post its privacy policy on its Web site.

(b) The term “conspicuously post” with respect to a privacy policy shall include posting the privacy policy through any of the following:

(2) A hyperlink to a Web page on which the actual privacy policy is posted and the hyperlink contains the word “privacy.” The hyperlink shall also use a color that contrasts with the background color of the Web page or is otherwise distinguishable.

(3) A text link that hyperlinks to a Web page on which the actual privacy policy is posted, if the text link is located on the homepage or first significant page after entering the Web site, and if the text link does one of the following:

(A) Includes the word “privacy.”

(B) Is written in capital letters equal to or greater in size than the surrounding text.

(C) Is written in larger type than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same size, or set off from the surrounding text of the same size by symbols or other marks that call attention to the language.

(4) Any other functional hyperlink that is so displayed that a reasonable person would notice it.

California’s common law is clear; you cannot bind a website user to inconspicuous contractual provisions contained in a document (terms and conditions and privacy policies) of which they are unaware and whose contractual nature is not obvious.

Although this is a California law, if residents from California can access and interact with your website, you are required to comply with these regulations regardless of the state in which you live.

What Does the FTC Say About Being Clear and Conspicuous?

If disclosures are essential to prevent your ad from being deceptive, the disclosure is required to be posted “clearly and conspicuously.” Just ask the more than 60 companies – including 20 of the 100 largest advertisers in the U.S. – that received warning letters from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) as part of its Operation Full Disclosure.

Whether or not your company received a warning letter from the FTC, there are some important lessons from the commission’s most recent effort to ensure that advertisers comply with long-standing advertising laws and regulations. The FTC found plenty of ads containing misleading claims that advertisers tried to “fix” with the usual fine print.

Even if your company didn’t get an FTC warning letter, it doesn’t mean your disclosures and disclaimers are ok. Smart website owners will use Operation Full Disclosure as a reminder of the “clear and conspicuous” rule.

Website Disclaimers and Disclosures

Disclaimers and disclosures, to be effective and to help protect you, must be posted “clearly and conspicuously.” Unlike provisions in a privacy policy or terms and conditions, some disclaimers, like medical and financial, if they are to help protect you, should be made available before users read, download, or buy products and services from you. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recommends that advertisers place their disclaimers or disclosures as close as possible to their claims or advertisements, the closer the better.

Post your disclosures clearly and conspicuously and do not include or hide them in your terms and conditions or privacy policies. The FTC encourages website owners to make their disclosures in the same way they try to attract customers—with larger print, graphics, color, clear wording, and conspicuous placement.

So, how big does the font size in a disclaimer or disclosure have to be? Six point, 10 point, 14 point? What’s better: Ariel or Times New Roman? How long do they have to show on a screen? We get such questions regularly. There are three important reasons why website owners and advertisers who focus on the details may be missing the big picture.

“Clear and conspicuous” is not a font size, it is a performance standard.

What qualifies as a clear and conspicuous disclosure? If a consumer visiting your website can see, read, and understand it. No website owner wants the FTC staff to dictate the specifics for their website advertising campaigns. Except for a few rules requiring specific disclosure standards, and so long as visitors leave your site with a clear understanding of your ads, website owners have significant leeway when marketing and complying with the clear and conspicuous rule.

Who knows better than advertisers how to convey information clearly and conspicuously?

Website owners can use almost endless methods to make their disclosures obvious to users. They often say, “We don’t understand how to make our disclosures clear and conspicuous.” Really? Website owners are masters at making their products and services clear and conspicuous. Well, they should use the same methods and set of tools, like text, sound, visuals, color, and contrast, for their disclosures, too.

Think about it a different way. How would you display a message on your website if you wanted—rather than were required to—display it? Consider your disclaimers and disclosures to be important information that you want to show to your users. Doing so makes it easier to comply with the clear and conspicuous rule. Make sure users of your website do not have to search for your disclaimers and disclosures; they should reach out and grab users’ attention.

What Does Google Say About Posting Your Disclaimers?

If you plan on using Google AdWords to advertise, you may be required to post disclaimers on pages of your website that make claims and on which you have testimonials. Where does Google say you need to place your disclaimers to comply with its guidelines?

“In a prominent location, above the fold of the page, with every claim linked to it by an asterisk (*) The link should be the same text font/color/size as the rest of the content.”

What Are Facebook’s Requirements for Posting Your Disclosures?

Facebook requires you to have disclosures in your privacy policy if you use its Custom Audiences or Conversion Tracking. If you use these services, you are required to have a “prominent link” from every one of your webpages where Facebook-generated pixels are placed linking to your privacy policy.

What if the Law or Federal Statute Does Not Precisely Define Terms?

When a law or federal statute leaves terms undefined or otherwise has a “gap,” we often borrow from state law in creating a federal common law rule. The Uniform Commercial Code’s (UCC) definition of “conspicuous” is the obvious choice because it is used to make contract language readily available to unsophisticated parties.

Here is a shortened version of the UCC’s definition of conspicuous:

“Conspicuous”, with reference to a term, means when written, displayed, or presented that a reasonable person would notice it. Whether a term is “conspicuous” or not is a decision for the court. Conspicuous terms include the following: (A) a heading in capitals equal to or greater in size than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same or lesser size; and (B) language in the body of a display in larger type than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same size, or set off from surrounding text of the same size by symbols or other marks that call attention to the language.

What Does Case Law Tell Us About Being Clear and Conspicuous?

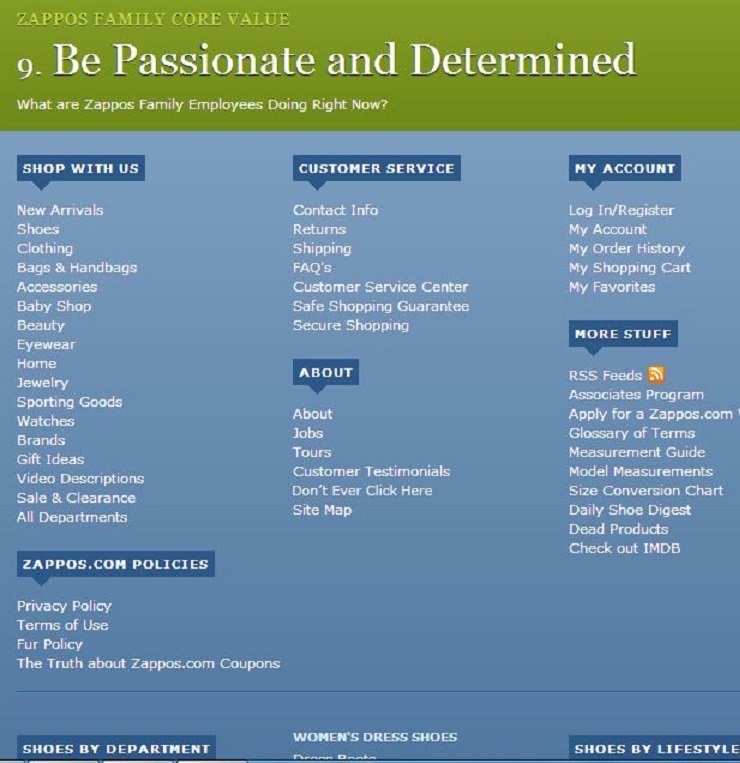

Zappos.com, Inc., Customer Data Security Breach Litigation (2012)

Here, the Terms of Use hyperlink can be found on every Zappos webpage, between the middle and bottom of each page, visible if a user scrolls down. For example, when the Zappos.com homepage is printed to hard copy, the link appears on page 3 of 4. The link is the same size, font, and color as 16 of the most other non-significant links. The website does not direct a user to the Terms of Use when the user creates an account, logs into an existing account, or makes a purchase. Without direct evidence that 21 plaintiffs clicked on the Terms of Use, we cannot conclude that the plaintiffs ever viewed, let alone manifested assent to, the Terms of Use.

The Terms of Use is inconspicuous, buried in the middle to bottom portion of every Zappos.com webpage, among many other links, and the website never directs a user to the Terms of Use. No reasonable user would have reason to click on the Terms of Use.

See how Zappos posted the link to its Terms of Use below:

Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp. (2002)

This is a case in the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit regarding the enforceability of browse-wrap software licenses. The court held that merely clicking on a download button does not show assent to license terms if those terms were not conspicuous and if it was not explicit to the consumer that clicking meant agreeing to the license.

The crux of the issue is whether or not the plaintiffs agreed to be bound by the defendant’s licensing terms when they downloaded the free plug-in, even though the plaintiffs could not have learned of the existence of the terms before downloading. The court found that “a reasonably prudent Internet user in circumstances such as these would not have known or learned of the existence of the license terms before responding to defendants’ invitation to download the free software, and that defendants therefore did not provide reasonable notice of the license terms”.

The Court holds that the act of downloading software does not indicate assent to be bound by the terms of a license agreement, where a link to such terms appears on, but below, that portion of the web page that appears on the user’s screen when such downloading is accomplished. As a result, the court holds that under California law, plaintiffs are not bound by the terms of such a license agreement, or the arbitration clause contained therein, despite language in the license agreement which provides that by installing or using the software, the user consents to be bound by the terms of the license agreement.

Koch Industries, Inc. v. John Does, 1-25 Defendants (2011)

(Finding there was no manifested assent where the “Terms of Use . . . were available only through a hyperlink at the bottom of the page, and there was no prominent notice that a user would be bound by those terms.”)

The plaintiff sought to premise the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act liability on its website’s Terms of Use, which provided: “No competitors or future competitors are permitted to access our site or information.” But, as with Koch’s website, the defendant took “no affirmative steps” to prevent such access. The website was “not password-protected, nor [were] users of the website required to manifest assent to the Terms of Use, such as by clicking ‘I agree’ before gaining access to the database. Rather, anyone … [could] access and search [the] information at will.”

Like Koch’s website, the Terms of Use did “not appear in the body of the first page” of the website; instead, “the link to access the Terms was buried at the bottom of the first page.” Accordingly, the site was “not protected in any meaningful sense by its Terms of Use or otherwise.

Cvent, Inc. v. Eventbrite, Inc. (2010)

Declining to enforce the “Terms of Use” where the “link only appears on Cvent’s website via a link buried at the bottom of the first page” and users of Cvent’s website are not required to click on that link, nor are they required to read or assent to the Terms of Use in order to use the website or access any of its content.

What is Inconspicuous?

One has only to look at the case law shown above to quickly learn how the courts describe the term “inconspicuous.” Such descriptions include:

• Buried in the middle to bottom portion of every webpage among many other links.

• Available only through a hyperlink at the bottom of the page.

• Buried link at the bottom of the first page.

Here is a perfect example of links to website policies and disclosures that are not clear and conspicuous. They use a hard-to-see, small, non-contrasting font buried in the footer of the website.

![]()

This happens to be the website of a multi-billion-dollar company known worldwide. Even more surprising is that just a few years ago, this company had a complaint filed against it and came under the scrutiny of the FTC for…guess what? In addition to not complying with the revised COPPA rule, several of the website’s links were not “clear and prominent.”

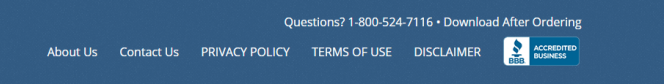

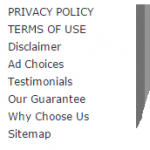

What is Conspicuous?

Positioning links to your documents above the fold of the page (so that users do not have to scroll), and making sure the font is at least the same size as the surrounding text. The following is an example of a privacy policy, terms and conditions, and disclaimer that are posted clearly and conspicuously:

The above sample happens to be in the header of the website. It does not make any difference if you put the links to your documents in the header of your website or on the left or right sidebar. Below is a sample of your privacy policy and terms of use being posted on the right or left sidebar in a clear and conspicuous manner.

The important thing is to keep the links above the fold of the page and follow the text size guidelines.

Can It Be Any More Clear and Conspicuous?

Time and again, we see words like “prominent link,” “clear and conspicuous,” and “obvious” being used to describe the posting requirements for disclosures, disclaimers, and privacy policies. These descriptions are used to help website owners comply with state laws, statutes, FTC regulations, Google’s and Bing’s terms of service, Facebook’s advertising policies, and those of other companies and some global regulatory agencies.

Conclusion

Although the law does not specifically define the term “Clear and Conspicuous,” there are enough state laws, regulations, and case law that make it clear how you should be posting your privacy policies, terms of use, disclaimers, and disclosures. Case law also makes it very clear what not to do.

Although most of the court cases cited here concern a website’s terms and conditions (terms of use), the same criteria apply to any website document whose intent is to bind a user or customer contractually.

SOURCES

http://goo.gl/hvKCSY

https://goo.gl/J4tfrH

http://goo.gl/OyAtW6

http://goo.gl/nN9iwM

http://goo.gl/eyiLqf

http://goo.gl/8sKUl3

http://goo.gl/eKnKLz

https://goo.gl/56aVEd

http://goo.gl/IDqmG

http://goo.gl/WgvTH

http://goo.gl/V33tCw